What Is The Fundamental Attribution Error?

It is impossible to value all the information we find every day, especially with the rise of the internet and social media. We must continuously make decisions based on the information we have or can look up. With so much information and so little time, we usually make quick decisions based on heuristics. This leads to biases, such as the fundamental attribution error (Gilbert, 1989).

The fundamental attribution error affects and distorts the attributions we make. It describes the tendency or predisposition to overestimate internal personal aptitudes or motives, when trying to explain or interpret the behavior of others, while understanding the importance of the environment.

The Castro Experiment

Edward E. Jones and Keith Davis (1967) designed a study to test how attributions work. In particular, they wanted to study the way we attribute criticism to an unfavorable attitude. Let’s take a look at this experiment to clarify this phenomenon.

In this experiment, certain participants were given a piece of text against Fidel Castro and other participants a piece of text in favor of Fidel Castro. They then asked the participants to describe the writers’ attitudes towards Fidel Castro.

The participants’ attributions were the same as how they were assigned in the pieces of text. They said that those who wrote in favor of Castro were for him, and those who wrote against him were against him.

So far, the results have been as expected. If they thought the writers had written openly, the attributions made were internal. Participants assumed that the writers had written from their own beliefs.

However, other participants were told that the writers had only accidentally written for or against Castro. The toss of a coin decided whether they would write for or against him.

With this new information, the researchers expected that the participants would now indicate external attributions. However, the attributions remained internal. If you write a positive piece, you are for it. If you write negatively about something, you argue against it, regardless of the motive from which you write.

It’s striking how the mind works, isn’t it?

Internal and external attributions

What are internal and external attributions? What is the difference between these? These attributions refer to reasons, or causes (Ross, 1977). An internal attribution is what makes a person, especially his internal characteristics, responsible for a result. These internal characteristics include attitude and personality.

For example, if someone I don’t like fails a test or is fired from their job, I will probably attribute it to internal causes. He failed because he is stupid, she was fired because she is lazy. Being stupid or lazy are stable characteristics of people.

On the other hand , the external attributions consist of the influence of situations, changes, and unsafe factors. Sticking with the previous example, if someone I like is fired, I might assume it’s because she was having a bad day or her boss is incompetent.

In this case, the attributes are based on indirect events, such as having a bad day or the internal characteristics of the third party.

Explanations for a Fundamental Attribution Error

There are several theories that try to explain how a fundamental attribution error arises. Although we don’t know exactly what is happening, there are a number of hypotheses. One of these theories is the “just world hypothesis” (Lerner and Miller, 1997).

According to this hypothesis , people get what they deserve and deserve what they get. When we attribute the faults of someone we don’t like to their personality rather than situational factors, it fuels our desire to believe in a just world. This belief confirms the idea that we have control over our own lives.

Another theory is that of actor’s communication (Lassiter, Geers, Munhall, Ploutz-Zinder, and Breitenbecher, 2002). When we pay attention to an action, an individual is the reference point.

We ignore the situation as if it were simply a background event. Thus, our attributions of behavior are based on the people we observe. When we observe ourselves, we are more aware of the forces around us. Therefore, external attributions.

Culture and the Fundamental Attribution Error

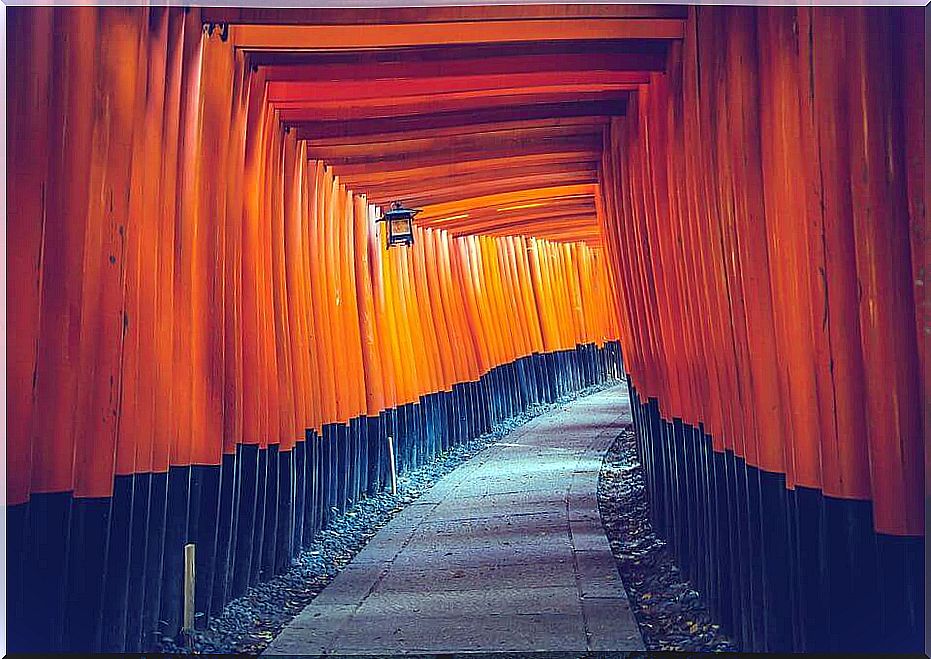

The fundamental attribution error is not the same all over the world. Researchers have found that it is more prevalent in individualistic cultures (Markus and Kiyatama, 1991).

People who are more individualistic have this bias more often than people from a collective culture. In this way, people from Asia attribute behavior more to situations, while Western people attribute the behavior to the person himself.

Culture can determine these differences. Individualists are more common in the west and see themselves as independent. As a result, they are more likely to see individual objects in relation to contextual details. In contrast, people from collective cultures pay more attention to the context.

A classic difference can be found in paintings. Western painters like to put people on a large part of the canvas, with less eye for depth. In countries like Japan, paintings show small human figures in detailed landscapes.

As we have seen, prejudices are hard to avoid because they are rooted in our culture. However, you can avoid them. Some ways to correct the fundamental attribution error are (Gilbert, 1989:

- Note the consensus information. If many people behave in the same way in the same situation, the situation may be the cause.

- Ask yourself how you would behave in the same situation.

- Look out for inconspicuous causes. In particular, factors that do not stand out.

Bibliography

Gilbert, D.T. (1989). Thinking lightly about others: Automatic components of the social inference process. In JS Uleman & JA Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 189–211). New York: Guilford Press.

Jones, E.E. & Harris, V.A. (1967). The attribution of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3, 1–24

Lassiter, FD, Geers, AL, Munhall, PJ, Ploutz-Snyder, RJ y Breitenbecher, DL (2002). Illusory causation: Why it occurs. Psychological Sciences, 13, 299-305.

Lerner, MJ & Miller, D.T. (1977). Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1030-1051.

Markus, H.R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. “In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 10, pp. 173–220). New York: Academic Press.